So you’ve heard about the Norwegian method and how athletes like Jakob Ingebrigtsen and Kristian Blummenfelt are crushing it with this approach. If not, feel free to check out our previous article on the Norwegian method of endurance training. There, we cover the science behind the Norwegian training method and how elite endurance athletes implement it into their training programs.

But a question we know you’re asking is: “How on earth do you structure a training year around such intense, quality-focused sessions? Don’t you burn out?”

That’s exactly what we’re diving into today. We’re pulling back the curtain on the secret sauce that makes the Norwegian Method sustainable and incredibly effective: its unique approach to periodization.

If the workouts are the ingredients, periodization is the recipe that tells you when to use each one. Get it right, and you’ll build fitness systematically while staying healthy. Get it wrong, and you’ll either burn out or show up to your key races undertrained.

Let me walk you through how the Norwegians structure their training year, and why it works so well.

What is Periodization?

Before we dive into the Norwegian-specific approach, let’s make sure we’re on the same page about what periodization actually means.

Periodization is simply the systematic organization of your training into specific phases or cycles throughout the year. Think of it like building a house. You don’t just randomly throw bricks and wood together. You pour the foundation first, then frame the walls, then add the roof. Each phase builds on what came before.

In endurance training, periodization typically involves:

- Macro-cycles: Your big-picture annual plan (usually 6-12 months)

- Meso-cycles: Medium-term blocks (typically 3-6 weeks)

- Micro-cycles: Your weekly structure

The goal is to gradually build your fitness, allow for recovery, peak at the right time, and avoid injury or burnout along the way.

Periodization Methods in Endurance Training

Before looking at how the Norwegian method structures training, it helps to understand the bigger picture. Endurance coaches organize training in different ways depending on the season, fitness level, and goals. These organizing styles are called periodization methods.

You’ll hear a few of them mentioned in running and triathlon circles. The names sound technical, but the ideas behind them are simple.

Linear (Traditional) Periodization

This is the classic “start easy, build gradually, peak once” model. You increase volume and intensity step by step over several months.

- Early season: lots of easy aerobic work

- Mid-season: more tempo, threshold, and longer intervals

- Pre-competition: higher-intensity intervals, race-specific sessions

- Race period: volume drops, intensity stays sharp

This approach works well for long build-ups, but it’s less flexible when you have many races or a busy schedule.

Block Periodization

Instead of doing a bit of everything every week, you focus deeply on one training quality at a time.

- 1–3 weeks of high focus on one area (e.g., VO₂max or threshold)

- Followed by a recovery or maintenance week

- Then move to the next block

It allows you to hit very high workloads in a specific zone without spreading yourself thin. Many elite endurance athletes use some form of this because the stimulus is strong and progress is measurable.

Reverse Periodization

This flips the traditional model. You start with intensity first, then layer in endurance later.

- Early season: short, fast, sharp sessions.

- Mid-season: longer intervals and threshold work, for example, cycling interval training.

- Closer to races: bigger volume and race-specific endurance

This is popular with triathletes training indoors in winter or time-crunched athletes who want to maintain top-end speed early.

Undulating (Non-Linear) Periodization

Here, the intensity and volume change more frequently, sometimes within the same week.

A week might include:

- A long, easy day

- A threshold day

- A VO₂max day

- A technique or strength day

This keeps the body adapting without long monotone phases. It’s a good fit for athletes who like variety or have unpredictable schedules.

5. Polarized Periodization

Also known as the “80/20” training model. Most training is low intensity, while a small but consistent portion is very high intensity.

- ~80% at easy effort

- ~20% hard (VO₂max, race-pace surges, hill intervals)

This builds a strong aerobic engine without constantly sitting in the “gray zone.”

6. Threshold-Focused Periodization

This style increases time spent just below the lactate threshold. It’s common in cycling and long-course triathlon. Think long, steady work at a “comfortably hard” pace. It’s great for improving sustainable race intensity.

7. The Norwegian (Double-Threshold) Approach

This method deserves its own category because it blends different periodization ideas organically. At a high level, it fits closest to block periodization, but with a twist:

- They use repeated threshold blocks (2–4 sessions per week)

- Often done as double threshold days

- Everything is controlled by lactate levels monitoring

- High-intensity work is minimal in the base phase

- Easy volume is very high

It’s not a strict linear, polarized, or block model. It’s a hybrid with very careful control of intensity and fatigue.

Now that you’ve seen the bigger picture, let’s look at how the Norwegian method structures training and why its version of periodization stands out.

How Do Coaches Use Periodization?

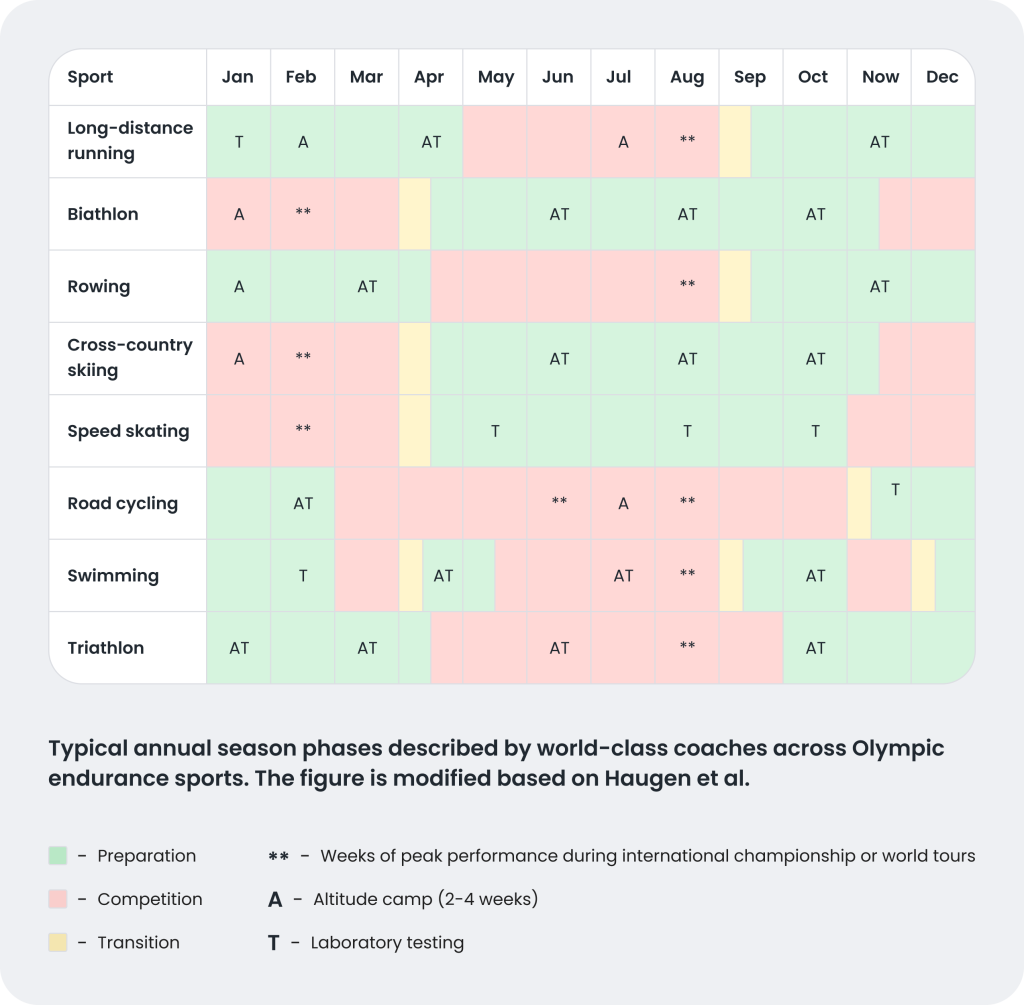

Here’s what’s interesting: when researchers surveyed world-class Norwegian coaches across multiple Olympic endurance sports, they found something consistent. These coaches all use traditional periodization principles, but they apply them pragmatically.

One coach explained their approach this way:

“Annual planning begins with creating a competition plan, working backward from the most important competition of the year, which is the Olympics or World Championships. The year is then divided into macro-, meso-, and micro-cycles before I begin the program planning… When planning the training, I apply the fundamental training principles, as well as principles and guidelines from traditional periodization. This means that I progress from general to specific training and increase the training volume before raising the intensity.”

Another coach noted:

“The basis for annual planning is Matveyev’s periodization with macro-, meso- and micro-cycles. During the year, we have three macro-cycles (competition periods), each with corresponding meso- and micro-cycles. We start with general training and progress to more intensive and specific training.”

What this tells us is simple: the best coaches in the world are using proven frameworks, but they’re flexible about how they apply them. As one coach put it, periodization gets adjusted “pragmatically to meet various constraints, such as competition schedule, altitude camps, access to facilities and snow/ice/water.”

The Norwegian twist isn’t what structure they use. It’s how they fill that structure with the right training at the right times. And that’s what we’ll explore next.

The Norwegian Method: Traditional Periodization with a Twist

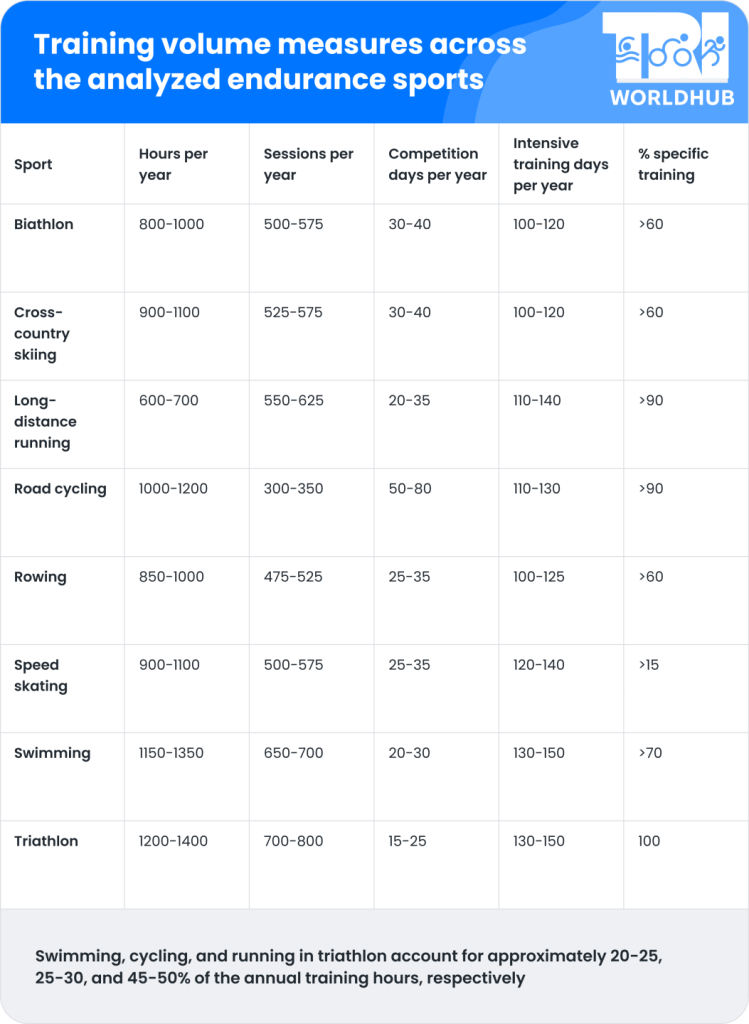

All Norwegian world-class coaches follow a traditional periodization model, which includes a gradual shift toward lower overall training volume and more competition-specific training as the competitive period approaches.

Wait, traditional periodization? Isn’t the Norwegian method supposed to be revolutionary?

Yes and no. The Norwegians aren’t reinventing the wheel when it comes to periodization structure. They base their annual planning on Matveyev’s periodization with macro, meso-, and micro-cycles, starting with general training and progressing to more intensive and specific training.

What makes the Norwegian method periodization special is how they apply intensity and volume within that traditional framework. The secret is in the details of each training phase.

The Norwegian Method flips the traditional model on its head. Instead of segregated phases, it employs what many experts call Integrated or Concurrent Periodization.

The key principle is this: You never completely abandon any key fitness component.

Instead of a “base phase” with only low-intensity work, or a “build phase” that forgets pure speed, the Norwegian approach weaves all the threads together throughout the year. It’s like a conductor ensuring the strings, brass, and woodwinds all play their parts in every movement of the symphony, just with varying emphasis.

- Aerobic capacity is always being developed with lots of moderate intensity training in Zone 1.

- Lactate threshold training is constantly being nudged with regular Threshold (Zone 3) sessions.

- VO2 Max is frequently stimulated with those signature hard interval trainings.

The volume and specificity of these sessions change as you approach your goal race, but the fundamental ingredients are almost always present in your weekly recipe.

Base Period: Building Your Aerobic Engine

The base period (also called the preparation period) is where Norwegian athletes do the heavy lifting, literally in terms of training volume.

Volume and Intensity Distribution

Norwegian distance runners run 120-180 km per week during the base period, with 70-80% done at low intensity. For triathletes, you’d scale this based on your discipline mix, but the principle remains: lots of easy work with complete intensity control.

Here’s what the week typically looks like:

Easy Training (Zone 1-2):

- Most of your training volume

- Heart rate around 62-82% of max

- Blood lactate below 2 mmol/L

- This builds your aerobic base without accumulating fatigue

Threshold Work (Zone 3):

- 2-4 lactate threshold sessions per week, often performed twice on the same day (the famous “double threshold” days)

- Heart rate 82-92% of max

- Blood lactate 2-4 mmol/L

- Done in interval format to accumulate more work at this intensity

- Usually scheduled on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays

Higher Intensity (Zones 4-5):

- One session per week in zones 4 or 5 during the base phase

- These might be hill sprints, short intervals at 800-1500m pace, or short sprints

- Longer intervals above the anaerobic threshold (92-97% HRmax) are rarely used during the base period

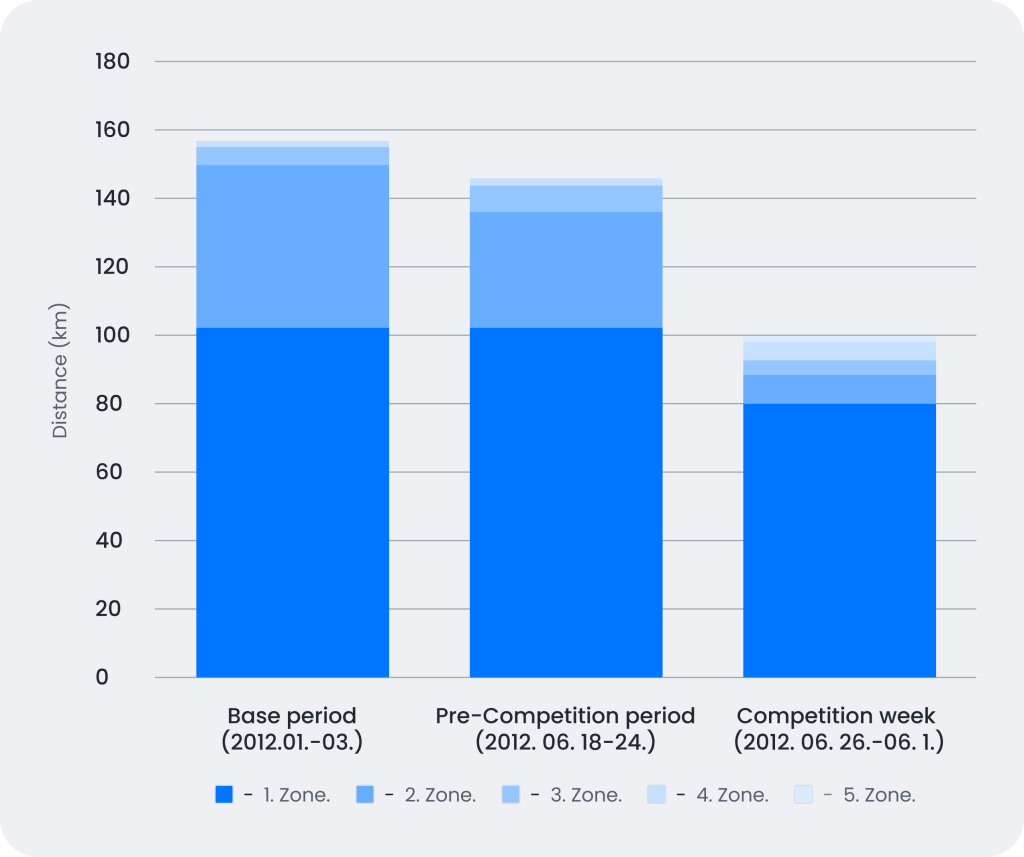

Here is an example of Henrik Ingebrigtsen’s, a Norwegian middle-distance runner, training load:

Why This Works

The goal of this base period is to develop the physiological foundation you’ll need later. Keeping most work easy and accumulating high volumes of threshold training without going too hard, allows atheltes to:

- Build aerobic capacity without excessive fatigue

- Develop lactate threshold systematically

- Maintain freshness for quality workouts

- Avoid the injury risk that comes from too much high-intensity work

As Marius Bakken notes, “within a single given time-frame the body is receptive for hard training. So it is a matter of finding how long this time-frame is, and utilizing it to the maximum“. The double threshold training days take advantage of this window without pushing into counterproductive intensities.

Pre-Competition Period: The Shift Begins

As you move from base training into the pre-competition phase (usually 4-8 training weeks before your key races), things start to change.

Volume Adjustments

Under the Norwegian model, training volume typically decreases from the base period. For example, Norwegian runners averaged 161 km per week in base training but reduced to 148 km during competition periods.

For triathletes, this might mean:

- Shorter long runs/rides/swims

- Fewer total weekly sessions

- More rest days or very easy recovery days

Intensity Shift

Here’s where Norwegian method periodization gets really interesting. Before the racing season, athletes do fewer workouts at anaerobic threshold speed and increase the number of sessions at specific race pace.

Practically, this means:

- Threshold workouts: Drop from 4 per week to 2-3

- Race-pace work: Increase sessions in zones 3-4 that match your target race intensities

- Double threshold days: May reduce from 2 per week to 1, or switch to single sessions

The goal is to maintain your threshold fitness while developing race-specific capabilities, essentially finding “how much you can allow your threshold speed to go down in the summer while at the same time working on race-specific factors“.

Triathlon coaches frequently apply “brick workouts” (combined sessions like cycling/running) to manage modality transitions and create physiological adaptations specific to racing. These become more prominent in the pre-competition phase.

Competition Period: Maintaining and Peaking

During the competition season, athletes like the Ingebrigtsen brothers use a low-to-high intensity volume ratio of 75:25 for non-race weeks and 80:20 for race weeks.

Notice what’s happening: when there’s no race, they maintain a bit more intensity work. When racing, they dial it back to stay fresh.

Your competition period training looks different:

- Easy volume: Remains high (75-80% of total) but with lower absolute volume

- Threshold work: Reduced to 1-2 sessions per week, often single sessions rather than doubles

- Race-pace work: Short, sharp sessions that rehearse race intensity without accumulating fatigue

- Recovery: Becomes even more critical, races themselves are hard workouts

Hard days like interval sessions are methodically alternated with easy low-intensity training days in between, with most coaches prescribing two to three hard days or key sessions weekly during base training. This rhythm becomes even more important during competition periods when races count as hard days.

Key Principles That Make The Norwegian Model Work

After looking at all this, you might be wondering: what makes the Norwegian method of periodization actually effective? Here are the core principles:

1. Progressive Overload with Patience

Coaches start with general training and progress to more intensive and specific training over time. They don’t rush the process. The base period is long and thorough.

2. High Volume, Controlled Intensity

The Norwegians figured out that by carefully keeping below the second lactate threshold, you can accumulate far greater training time at an intensity that’s still challenging enough to spur useful adaptations, with fatigue being four to five times greater for exercise 10 percent above the critical threshold than for 10 percent below it.

3. Strategic Timing

Double threshold sessions, both morning and afternoon, are applied twice a week during preparation training, with blood lactate concentrations in the range of 2-4.5 mmol/L. The timing also matters: at least 5 hours between sessions allows recovery while staying in that productive training window.

4. Individualization Within Structure

All coaches have primarily adjusted their training session models to the individual athlete and sport-specific demands, rather than based solely on general principles of lactate testing and double threshold training. The framework is consistent, but the details flex based on your needs, responses, and goals.

5. Quality Over Heroics

An all-out approach limits accumulated load and increases the odds for overtraining due to physical and mental strain. The best practitioners are cautious not to overuse all-out intensive sessions or introduce them too early. Controlled, semi-exhausting intervals done consistently beat occasional heroic efforts.

Where to Go From Here

Understanding the Norwegian method of periodization gives you the framework for organizing your training year. You now know:

- Why does the base period emphasize volume and threshold work

- How to shift focus in the pre-competition phase

- What competition-period training should look like

- The principles that make this approach effective

But knowledge alone won’t make you faster. The next step is implementation. You need to actually structure your weeks and workouts to follow these principles.

In the next article in this series, we’ll dive into the practical details: specific workout examples, how to set up your training zones, weekly schedules you can follow, and how to adjust the Norwegian method to triathlon training and your specific circumstances as an age-group triathlete.

The periodization framework you’ve learned today is the map. Now we need to walk the path.