Here’s something that confused me when I first learned about the Norwegian method: these athletes have incredible endurance (we’re talking world-class performances in events lasting hours), but they’re not doing keto. They’re not training fasted. In fact, they eat loads of carbohydrates. So how are they building the kind of fat-burning capacity that lets them race for 8, 10, or 15 hours without hitting the wall?

If you’ve been around triathlon culture for any length of time, you’ve probably heard two seemingly contradictory messages.

On one side, there’s the low-carb crowd talking about fat adaptation through dietary restriction: keto diets, fasted training, cutting carbs to “teach your body to burn fat.”

On the other side, you see elite Norwegian athletes dominating endurance events while eating what looks like a high-carb diet. Both groups talk about fat adaptation, but they seem to be doing completely opposite things.

The answer to this puzzle is simpler than it seems, but it requires us to rethink what fat adaptation actually means and how we develop it. The Norwegian method produces exceptional fat-burning capacity, but it does so through training strategy, not dietary restriction.

In this article, we’re going to explore what fat adaptation is for endurance athletes and how that works: how you can train your body to burn fat more efficiently at race pace while still eating the carbs you need to train hard and recover well.

What Fat Adaptation Actually Means (And What It Doesn’t)

Let’s start by clearing up what fat adaptation actually is, because there’s a lot of confusion around this term.

Fat adaptation isn’t a high-fat diet, as many might think about it. And it is not eliminating carbohydrates from your diet or turning yourself into a ketone-burning machine. Instead, fat adaptation means your body gets better at using fat intake as fuel, especially during long workouts.

That’s it.

Normally, your body prefers carbs because they’re a quick way to replenish your energy levels. But when you regularly train with lower carb availability (for example: fasted sessions, not eating during easy workouts, longer gaps between meals), your body learns to tap into stored fat more efficiently.

What changes with fat adaptation?

- You burn fat earlier and at higher intensities than before.

- You rely less on glycogen, so you last longer before “bonking.”

- Your energy feels more stable during long sessions.

Fat adaptation is not:

- Following a ketogenic diet

- Low-carbohydrate diet

- Becoming a “ketone-burning machine.”

Fat adaptation is completely different from ketosis. You don’t need a low-carbohydrate dietary strategy. You’re simply training your metabolism to use fat more effectively alongside carbohydrates.

Why do fat adaptation strategies matter for triathletes?

Consider an Ironman distance race or any other prolonged exercise. You’re out there for anywhere from 8 to 15-plus hours, depending on your pace. Your body can only store about 1,800 to 2,000 calories’ worth of carbohydrates, even when fully loaded. That’s maybe two to three hours of racing at moderate intensity if carbs were your only fuel source. If you can only burn carbohydrates efficiently, you’re going to bonk, no matter how many gels you consume. The gut can only absorb so much.

But if you can burn fat well at your race pace, let’s say you’re humming along on the bike at a steady aerobic effort, you extend your endurance dramatically. You might be burning 0.8 grams of fat per minute alongside your carbohydrate use. Over five hours on the bike, that’s significant energy coming from fat stores, which means you’re preserving those precious carbs for when you really need them: the hills, the run, the final push.

The goal is to burn more fat at the intensities where it’s possible, so that when you hit threshold or need to surge, you still have carbohydrates available. That’s what fat adaptation actually means for endurance athletes, and that’s exactly what the Norwegian method trains you to do.

The Norwegian Approach to Fat Adaptation: Zone 2 and FatMax

The real secret to Norwegian-method fat adaptation is deceptively simple: enormous amounts of time spent at low intensity.

Using a 5-zone training model:

- Zone 1: Recovery (50-60% max HR)

- Zone 2: Aerobic base (60-70% max HR)

- Zone 3: Tempo (70-80% max HR)

- Zone 4: Threshold (80-90% max HR)

- Zone 5: VO2max and above (90-100% max HR)

Norwegian athletes spend roughly 80-85% of their training time in Zones 1-2. We’re talking 15-20+ hours per week at conversational pace. While their famous 4×8 threshold intervals get attention, the real work happens during long, easy sessions.

At low intensities, your body naturally relies more on fat for fuel. There’s no need to force fat metabolism by restricting carbs. The physiology takes care of it. The key is spending enough time at these intensities to actually train the system.

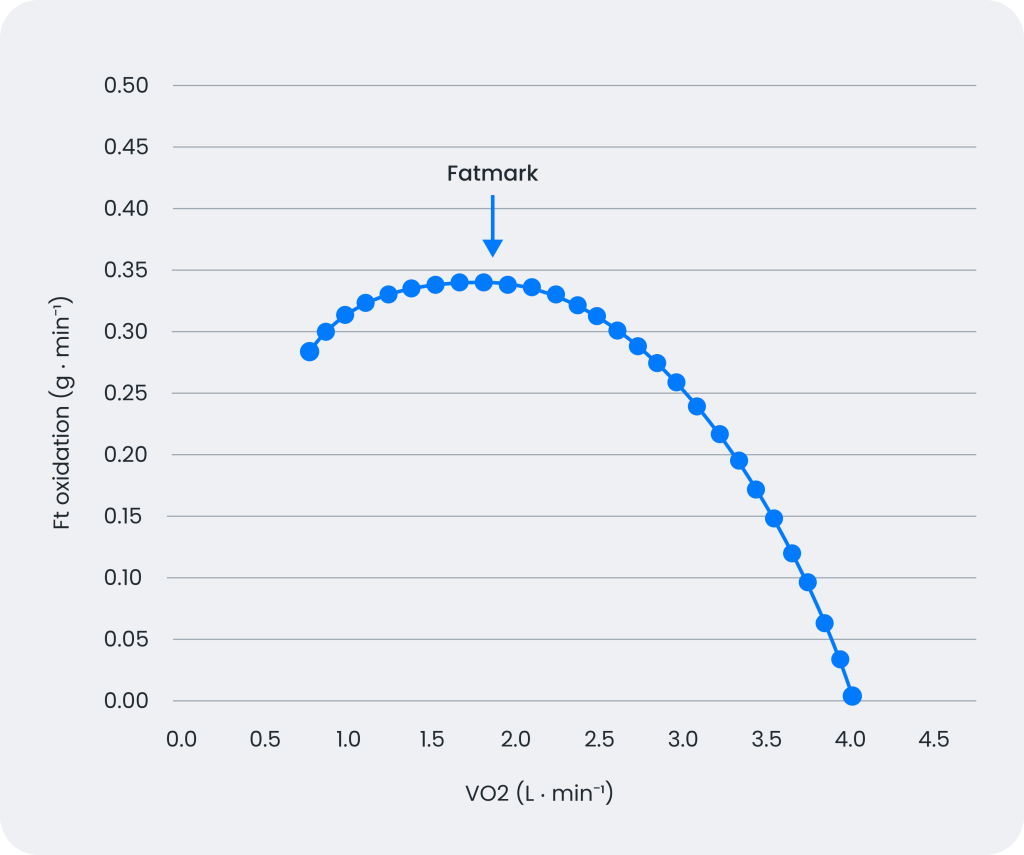

This is where the idea of the FatMax concept comes in. FatMax is the intensity at which your body burns the most fat per minute. Research on 300+ endurance athletes found that maximal fat oxidation typically occurs around 45-55% of VO2max (roughly corresponding to upper Zone 1 to lower Zone 2 in heart rate terms, though this varies individually). At this “sweet spot,” well-trained endurance athletes can burn 0.6-1.0+ grams of fat per minute.

When increasing exercise intensity, as well-trained athletes train in Zone 3 and above, carbohydrate metabolism increasingly dominates, and fat oxidation drops. This is why Zone 2 work is so valuable: you’re training right in the range where fat burning is naturally maximized.

The Cellular Adaptations

Spending 15-20 hours weekly at these intensities triggers profound changes inside your muscles:

- Increased mitochondrial density – more “powerhouses” producing energy

- Enhanced fat-oxidizing enzymes – better capacity to break down fat

- Improved fatty acid transport – easier movement of fat into muscle cells

- Greater capillary density – better oxygen delivery to muscles

You don’t need special hacks. You need time at the right intensity, patience, and consistency—the same principles guiding every aspect of the Norwegian approach.

The Norwegians spend a huge amount of time here. While their famous 4×4 intervals get all the attention, the real story is that they might spend 80% of their training week doing work at these lower intensities.

That’s 15–20 hours a week of teaching the body to burn fat efficiently.

Over time, this easy volume triggers big changes inside the muscle. You build more mitochondria — the powerhouses that produce energy. You increase the enzymes that break down fat and improve the transport of fatty acids into your muscle cells. Slowly, your internal engine becomes better at using fat as a steady, reliable fuel.

You don’t need special hacks to reach this point. You need time at the right intensity, patience, and consistency — all the same principles that guide the Norwegian approach from the ground up.

VLamax and Metabolic Flexibility: The Deeper Sport Science

There’s a concept in exercise physiology that helps explain why the Norwegian method works so well for the fat adaptation process, and it’s called VLamax. It sounds technical, but understanding it, even at a basic level, can change how you think about your training demands and exercise performance.

VLaMax estimates how quickly your body can produce energy through glycolysis (using carbs) — i.e. how “carb-dependent” your muscle metabolism tends to be.

When it’s high, even sub-maximal efforts involve more lactate production and carbohydrate use, which suppresses fat burning. When it’s lower, the body tends to rely more on aerobic (fat + oxygen) processes, which favors endurance and fat oxidation during long efforts.

VLamax stands for the maximum rate of lactate production, but you can think of it more simply as your glycolytic power. It’s a measure of how quickly you produce lactate, which is really a measure of how quickly you burn through carbohydrates via the glycolytic pathway.

If you have high VLamax, you’re a carb-burning machine. That’s great if you’re a sprinter or if you need explosive power for short efforts. But for prolonged exercise, especially for events lasting hours, high VLamax becomes a problem.

Here’s why: if your VLamax is high, you rely heavily on carbohydrate metabolism even at moderate intensities. You’re constantly tapping into glycolysis when you don’t really need to. This means you burn through your limited carbohydrate stores faster, you produce more lactate during low and moderate-intensity exercises, and your ability to oxidize fat at race pace is compromised.

Your aerobic threshold (the highest intensity you can sustain purely through aerobic metabolism) ends up being far below your anaerobic threshold. There’s a big gap between them, and that gap represents wasted potential.

On the other hand, if you have a lower VLamax, you can oxidize fat better at higher intensities. Your body isn’t defaulting to carb-burning at every opportunity. Your aerobic threshold creeps closer to your anaerobic threshold, which means you can sustain higher intensities aerobically. You become more metabolically flexible and able to use fat when appropriate and carbs when necessary.

The Norwegian method addresses VLamax specifically through its training structure. High-volume Zone 2 training actually lowers VLamax over time. You’re training your body away from relying on glycolysis by spending hours and hours using predominantly aerobic, fat-based metabolism. Your body adapts by becoming less glycolytic and more oxidative.

The threshold work in the Norwegian method is also carefully controlled to support this. Remember the lactate-guided intervals we discussed in previous articles?

Those sessions are designed to work at or just below the lactate threshold, meaning you’re staying aerobic. You’re not doing a lot of work that’s deeply anaerobic, which would train up your glycolytic system and raise VLamax. Unlike many training programs that include frequent high-intensity intervals well above threshold, Norwegian athletes do comparatively little work in Zone 5. This prevents “training up” the glycolytic system.

Nutrition matters a lot for fat adaptation. Fat-adapted athletes don’t have to cut all carbs — they just use them smartly. Give your body carbs when you have a hard workout, because you need the energy.

But during easy sessions, you don’t need to overload on carbs. Training with slightly lower carb levels helps your body get better at burning fat.

Now, here’s the practical reality: you can’t easily measure your VLamax without lab testing and specialized equipment. Most athletes don’t have access to that. But you can train in ways that lower it, which is really what matters.

The formula is straightforward: consistent, high-volume, easy work combined with controlled threshold training and minimal truly anaerobic efforts. That’s the Norwegian method in a nutshell, and it’s a training approach that systematically lowers VLamax and improves fat oxidation capacity.

You might notice the effects over time without ever measuring VLamax directly. If you find yourself able to hold faster paces at lower heart rates, that’s a sign your aerobic system is improving, and VLamax is likely decreasing.

If you can sustain tempo efforts that used to feel hard with less sense of strain, that’s your body becoming more aerobically efficient. If you’re getting through long training sessions, for example, excessive strength training, or an interval cycling training without feeling like you’re constantly depleting your carb tank, your fat oxidation is improving.

The key insight here is that metabolic flexibility, the ability to burn fat well when appropriate and switch to carbs when needed, is about systematically developing your oxidative capacity while managing your glycolytic system.

This is sophisticated training, but it doesn’t require sophisticated equipment to implement. You just need to understand the principles and apply them consistently.

Training Fasted vs. Fueled — When and Why

Let’s address the elephant in the room: what about fasted training? If you’ve been reading about fat adaptation anywhere online, you’ve probably seen people swearing by training without breakfast, doing long rides on empty, and generally avoiding carbs before workouts. So where does this fit into the Norwegian method?

The short answer is: the Norwegian approach is generally cautious about fasted training, but there’s some nuance here worth understanding.

The core principle is this: fat adaptation in the Norwegian method comes primarily from volume at the right intensity, not from training in a depleted state. You’re building the adaptation through sheer accumulated hours in Zone 2, where fat oxidation is naturally high. You don’t need to add the stress of training fasted to get the benefit. The training stimulus alone is sufficient.

That said, some Norwegian-method athletes do use strategic fasted or low-carb training for specific sessions. The key word is strategic, meaning occasional, purposeful, and carefully applied. Here’s when it might fit:

For selected easy Zone 2 sessions, some athletes will do a short morning run or ride fasted. We’re talking 60 to 90 minutes maximum, truly easy pace, and only when the athlete is well-rested and not in a heavy training block. The idea is that training with lower muscle glycogen content might enhance some of the cellular signals for mitochondrial adaptation. There’s research suggesting this can amplify the oxidative training response.

But notice the caveats: short duration, easy intensity, and not done chronically. This isn’t about doing all your training fasted. It’s about occasionally adding a mild metabolic stress to specific easy sessions.

Here’s when you should absolutely fuel your training: any threshold or interval work. Period. Those 4×4 sessions, tempo runs, race-pace efforts — these all require adequate carbohydrate availability. If you try to do high-intensity work in a fasted or depleted state, the quality suffers dramatically. You can’t hit the prescribed intensities, your lactate response is abnormal, and you’re essentially wasting the session.

You should also fuel for long sessions — any endurance performance over two hours. Yes, even if it’s an easy pace. When you’re out for three or four hours, training fasted becomes counterproductive. You’ll fatigue prematurely, your form will break down, stress hormones will spike, and recovery will take longer.

Double training days require fuel as well. If you’re doing a morning session and an afternoon session (a common pattern in Norwegian-style training), you need carbohydrates between sessions for sustained energy expenditure. Trying to do two workouts in a depleted state is a recipe for digging yourself into a hole.

And during heavy training blocks, when you’re logging high weekly volume, chronic under-fueling will destroy your adaptation. You’ll get run down, sick, or injured. The very training that builds fat adaptation in endurance training requires that you’re well-fueled enough to actually complete it.

Here’s the balance that makes sense: fat adaptation in the Norwegian method comes from the structure of the training itself: massive Zone 2 volume, controlled threshold work, and appropriate recovery.

A few strategic fasted easy sessions might add a small benefit for some athletes, but they’re not necessary, and they’re certainly not the foundation. If you want to experiment with an occasional fasted easy run, go ahead. But if you’re chronically under-fueling your training in the name of increased fat utilization, you’re working against yourself.

Lactate-Guided Training and Fat/Carb Combustion Rates

One of the most sophisticated aspects of the Norwegian method is how coaches and athletes measure and track fat adaptation. They’re using lactate testing and metabolic analysis to understand exactly what’s happening in the body at different intensities, and this data guides both training zones and training nutrition strategy.

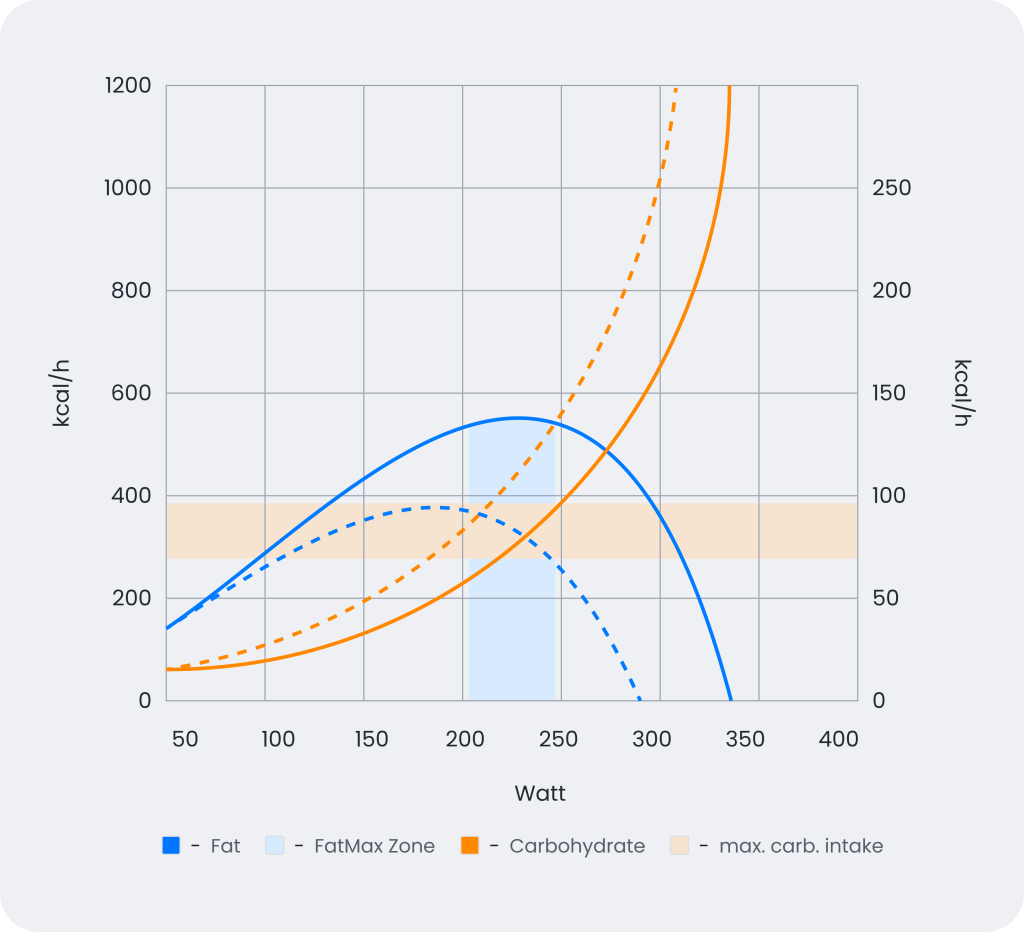

The tools are relatively straightforward. Athletes undergo lactate testing at progressive intensities, essentially a step test where blood lactate is measured at increasing workloads. This reveals the lactate curve and shows precisely where the athlete shifts from predominantly fat-based to carb-based metabolism. Modern athletic performance software can then project “Fat Combustion” and “Carbohydrate Combustion” rates at different intensities based on this data.

What does this look like in practice? Research on athletic populations shows significant variation in fat-burning capacity. A study of 1,121 athletes found that maximal fat oxidation averaged 0.59 grams per minute, with a range from 0.17 to 1.27 grams per minute PubMed. That’s a massive spread. The best fat burners were oxidizing more than seven times as much fat as the poorest.

Let’s put those numbers in practical terms. Imagine two trained athletes riding at tempo pace during an Ironman. Athlete A, who’s well-adapted, burns fat at 0.9 grams per minute. Athlete B, less adapted, burns fat at 0.4 grams per minute.

Over a five-hour bike leg, Athlete A oxidizes an additional 0.5 grams per minute compared to Athlete B. That’s 150 grams of fat over 300 minutes, about 1,350 additional calories coming from fat stores rather than from limited carbohydrate stores or race nutrition. That difference can literally determine whether you finish strong or hit the wall.

Here’s what the research tells us about training adaptations: in the athletic population studied, maximal fat oxidation occurred at an average exercise intensity of 49.3% of VO2max. This aligns almost perfectly with Zone 1 training in the Norwegian method. When you’re training at a conversational pace, you’re right in that sweet spot where fat oxidation is naturally high.

The adaptations from consistent training are substantial. Trained endurance athletes demonstrate increased capacity to oxidize fat at higher exercise intensities, with fat oxidation reaching peaks of 1 gram per minute during ultra-endurance exercise BioMed Central.

Elite athletes who’ve spent years building their aerobic systems through high-volume training can sustain these impressive fat oxidation rates even at relatively high intensities, intensities where untrained individuals would be burning almost exclusively carbohydrates.

Norwegian athletes and coaches use this metabolic data strategically. After a base-building phase focused on high Zone 2 volume, follow-up testing typically shows improved maximal fat oxidation rates and a rightward shift in the fat oxidation curve, meaning the athlete can burn fat effectively at higher intensities than before. This is objective confirmation that the training is working.

For age-groupers without lab access, you can’t get exact numbers, but you can track indicators of improving fat adaptation over time:

Can you go longer at a steady pace without needing to fuel? If you used to need a gel every 45 minutes on long rides and now you can go 90 minutes comfortably, that’s a sign your fat oxidation has improved.

Is your heart rate lower at the same pace? If your Zone 2 runs that used to sit at 145 bpm are now happening at 138 bpm, your aerobic system is becoming more efficient, likely including better fat utilization.

Do you feel less depleted after long, easy sessions? Better fat adaptation means you’re preserving more muscle glycogen stores, so you should recover faster and feel less wiped out after volume work.

Can you maintain higher intensities before feeling that urgent “I need carbs now” sensation? Well-adapted athletes can sustain tempo efforts longer before their bodies start screaming for glucose.

The beauty of the lactate-guided approach used in the Norwegian method is that it removes guesswork. Instead of assuming you’re in the right zone for fat adaptation, you know. Instead of hoping your base training plan is working, you can measure it. And instead of following generic fueling recommendations, you can tailor your sports nutrition to your actual metabolic profile.

This precision extends to race strategy as well. If testing shows you can maintain 0.8 grams per minute of fat oxidation at race pace, you can calculate more accurately how many carbs you’ll actually need during the race. You’re not over-fueling and risking GI distress, and you’re not under-fueling and bonking. You’re matching your fueling strategy to your actual metabolic capacity.

Smart Fueling Strategy for Fat-Adapted Training

Fat-adapted athletes don’t eliminate carbohydrates. They use them strategically for better low-carbohydrate performance. Here are a few rules that are worth exploring:

Fuel hard workouts:

- Threshold sessions, intervals, and race-pace work all require adequate carbohydrate availability.

- Eat 1-3 hours before these sessions (timing depends on individual digestion).

- Include easily digestible carbs: oatmeal, banana, white rice, sports drinks.

Go easier on carbs during easy sessions: For Zone 2 work, you don’t need to pre-load heavily. Your body will preferentially burn fat at these intensities. Some athletes train these sessions in a moderate carbohydrate state (not fully fasted, but not heavily fueled). This may enhance fat oxidation signaling.

Always fuel long sessions: Anything over 2 hours needs carbohydrate intake during the session, even at an easy pace. Target 30-60g per hour, depending on intensity and individual tolerance.

Prioritize recovery nutrition: After hard sessions, replenish glycogen with carbohydrates within 30-90 minutes. This ensures you’re ready for the next quality workout.

Sample fueling day (heavy training):

- Morning Zone 2 ride (90 min): Light breakfast or just coffee, water during ride

- Lunch: Normal mixed meal with carbs, protein, and vegetables

- Afternoon threshold session (60 min): Pre-fuel 90 minutes before with a banana and energy bar

- Post-workout: Recovery shake or meal with 3:1 or 4:1 carb-to-protein ratio

- Dinner: Substantial carbohydrates to replenish stores

Tracking Your Fat Adaptation Progress

While Norwegian athletes use blood glucose testing and metabolic characteristics analysis to measure fat adaptation precisely, you can track meaningful indicators without lab access.

Self-Assessment Methods

1. The 2-Hour Zone 2 Test

- Do a Zone 2 ride or run with only water (no fuel)

- Note when you first feel you genuinely NEED food (not just want it)

- Retest monthly, improving fat adaptation means you can go longer comfortably

2. Heart Rate at Fixed Pace

- Track heart rate for a standard Zone 2 workout (same route, same pace)

- As fat adaptation improves, heart rate should decrease at the same pace

- Example: Your regular 10-mile Zone 2 run at 9:00/mile pace drops from 145 bpm average to 138 bpm over 8-12 weeks

3. Aerobic Decoupling

- Compare the first-half to the second-half heart rate during long Zone 2 sessions

- Calculate: (HR second half / HR first half – 1) × 100

- Less than 5% = excellent aerobic efficiency

- Improving decoupling over time indicates better fat utilization

4. Perceived Effort Stability

- During 2-3 hour Zone 2 sessions, does your perceived effort stay stable?

- Better fat adaptation means steady perceived effort rather than a gradual increase

- You should finish feeling like you could continue, not depleted

5. Recovery Speed

- How quickly do you recover from long Zone 2 sessions?

- Improved fat oxidation preserves more glycogen, enabling faster recovery

Fat Adaptation for Endurance Athletes: Pulling It All Together

The Norwegian method builds exceptional fat-burning capacity through training structure, not dietary tricks. The formula is straightforward but requires commitment:

1. Massive Zone 2 training volume (80-85% of training time)

2. Controlled threshold work (lactate-guided, limited volume)

3. Minimal anaerobic training (avoid excessive Zone 5 work)

4. Strategic fueling (match carbs to session demands)

5. Patience and consistency (8-12+ weeks for measurable adaptation)

This approach systematically lowers VLamax and shifts your metabolic flexibility toward greater fat utilization at race-relevant intensities.

You don’t need laboratory testing to implement these principles, just a heart rate monitor, discipline to stay in Zone 2, and the patience to let adaptations develop over weeks and months.

The result: you’ll be able to sustain longer efforts at higher intensities while preserving precious carbohydrate stores for when you truly need them. That’s something that’s available to any endurance athlete willing to embrace high-volume, low-intensity training.

Start with where you are now, build volume progressively, stay disciplined with intensity, fuel intelligently, and trust that consistent Zone 2 work creates the adaptations you’re seeking.